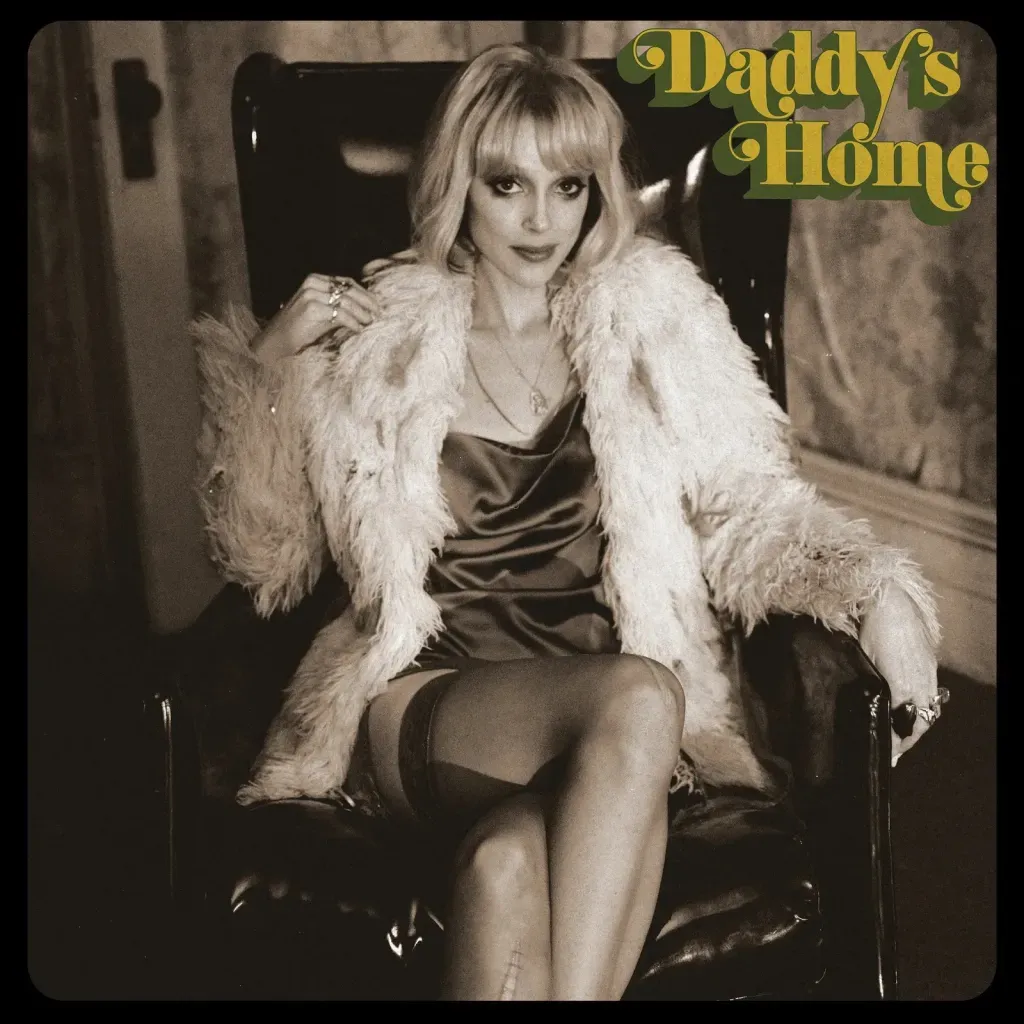

St. Vincent, Daddy’s Home.

Stereodista ponders St. Vincent, her new LP, Daddy’s Home, and David Bowie.

“You can’t steal from a thief,” said the late greatest, David Jones, to James Murphy (of DFA, LCD, etc.) when the latter fessed up to having nabbed a bit or two from the former’s oeuvre for his own. Or so the apocryphal story goes, at any rate. Jones himself – marginally better known by his stage name, David Bowie – is often viewed as a musical chameleon or magpie, and quite clearly: from psych to soul, Krautrock to crackpot, whether this should be aurally or visually, he was never one to rest on his laurels. Yet what he didn’t so much rest as rely on, was the work of those who’d gone before him – whether that be The Velvet Underground or Neu!, or many another between the two. This is no secret, is something that Bowie was both really cognisant and readily accepting of, and has been regurgitated ad nauseam. So I won’t dwell on it unduly. But I bring Him in because central to His unpredictable caprice was a will to astound and confound with every record, and this was achieved via an all-encompassing sense of artistry — pinching sounds and styles, personae, and so on. Which is something that Annie Clark – aka St. Vincent – also strives to do.

Clark, much like Bowie, succeeds for the most part. And, akin to her Bromley analogue, began with a rather more demure release than she’s now renowned for: Marry Me (and, to a lesser extent, Actor) are far cries from the histrionic riffs and comparably ostentatious sartorial choices since, in much the same way that David Bowie (and, to a lesser extent, The Man Who Sold the World) differ from any and every LP which followed. St. Vincent, her fourth if first eponymous effort, echoed the palette of Aladdin Sane and played into similarly ethereal imagery, before MASSEDUCTION saw her lampoon the pin-up concept in a striking blaze of Day-Glo glory. The accompanying music was developing all the while, at times in wondrous synchrony with the otherworldly mien, and jarring in an intriguingly dissonant fashion at others. MASSEDUCTION – her most digitised album to date – was rewired not once but twice, as both pared-down, pianistic slow-down and high-octane remix compilation, demonstrating not only the quality, but so too the versatility of the songwriting on show.

Up until this point, the discographic trajectory of St. Vincent makes sense. This isn’t to say it’s too readable or boring; anything but. But it’s traceable: from Your Lips Are Red, to Marrow, to Cruel, to Rattlesnake, to Sugarboy, beneath the given veneer lies Clark’s highly legible, idiosyncratic signature. Yet this isn’t so much the case when it comes to Daddy’s Home – a first original release in the better part of four years – as she knowingly winks back at the ’70s, and perhaps her parents’ record collection, for inspiration. (Not that it necessarily needs saying, but for the purposes of this particular review if nothing else, there’s a neat tie-in with this being Bowie’s heyday decade when “Daddy” would’ve been in his early 20s.)

The album begins with Pay Your Way In Pain, which pretty unapologetically apes Fame, as well as onetime Prince collaborator Nikka Costa’s Like a Feather. “The show is only gettin’ started,” Clark reassures; the issue with this one is that it doesn’t necessarily sound like it’s hers. Not unlike Bowie’s ephemeral flirtation with so-called “plastic soul” from ’75 (Young Americans, from which Fame is of course lifted), it’s lacking in character in more ways than one; which, to reiterate, has proven one of Clark’s greater strengths thus far. It’s a repeat problem, and of offence: Down and Out Downtown hears Clark tell of a “joker with that funny laugh [who’s] diggin’ through the basement of [her] past,” atop what sort of sounds like Air rephrasing Robbie Williams and Kylie Minogue’s Kids, and comes accompanied by incongruous sitar twangs. None of which sounds much like Clark’s past to me, personally. (Nor the ’70s for that matter, sitar aside.)

Elsewhere, there are meandering soul moments (Daddy’s Home for one; My Baby Wants a Baby, which pilfers from Sheena Easton’s 9 to 5 (’81) so faithfully that Florrie Palmer receives a writing credit, another), although these have incontrovertibly been done better by, say, Natalie Prass on her exemplary self-titled début. Live in the Dream is suitably oneiric enough, but it’s basically Us and Them with sly lyrical nods to Comfortably Numb, before The Melting of the Sun incinerates any lingering doubts as to whether this is as flagrant Pink Floyd plagiarism as it sounds, as Clark directly references “the dark side of the moon” in its second line, and transports us back to ’73 in the process.

There are better moments, though; some much better moments. Tapping into Bowie’s penchant for Dadaism and such, The Laughing Man rebukes saccharinity (“Little birds ... singin’ like the day is perfect/ But to me, they sound psychotic”) and riffs on Father John Misty-eyed reminiscences of youth (“Half-pipes and PlayStations/ Suicidal ideation”) over a disorientating musical track featuring both mellotron and vibraphone, which proves redolent of the Manics’ S.Y.M.M. “I know you’re gone, you dropped the scene/ Left all of your guitars to me/ But I can’t play/ I know you know exactly what I’m sayin’” she continues, and while we all know full well how well she can – we’ve all seen Annie play – electric guitar lends an immediate, direct tonality which is gravely lacking from Daddy’s Home.

Slinky licks tongue Down – a decidedly combative track, which gives about as good as the album gets – and while its sitar line brings Justin Timberlake’s What Goes Around...Comes Around, well, all the way back around, Clark’s prints stampede all over it otherwise. Acoustically finger-picked and lyrically unresolved, Somebody Like Me may not be classic St. Vincent (which I would contend Down could well be), but it certainly adds a string to her proverbial bow. Likewise, ...At the Holiday Party is quite unlike Clark’s every previous, yet it strikes an inviting middle-ground between soul review and contemporary malaise (“Pills, and JUULs, and speed/ Your little purse a pharmacy”) to construct something which hark’s back to bygone times while looking forward, and may yet be considered ‘a classic’ irrespective of its authorship.

Scooping pieces of the old in order to mush together the the new is in no way novel, as Bowie knew only too well. But to manipulate the past in such a way so as to conjure something meritorious in and of itself is, some may argue, modern-day artistry condensed down into its crudest form. When this coincides with the release of your father – referred to as “inmate 502” on a loose, slightly louche title track – from prison, it’s made all the more so. For having been put away for stock market manipulation (the thief!) in 2010 – so between Actor (’09) and Strange Mercy (’11) – he missed St. Vincent’s respective heyday decade to date. And while Clark does herself miss the mark a fair bit this time round – much of Side A feels like a slow warm-up for Side B, which in turn seems more original – Daddy’s Home nonetheless makes for an interesting chapter, to which many writers besides Clark and Jack Antonoff can undoubtedly put their name.